Luke 19:1-10

Almost half my lifetime ago, I left my newspaper editor’s job in cold, wintery Bismarck, N.D., to serve overseas as a Peace Corps volunteer. I ended up in Kenya, in Eastern Africa, where Peace Corps, at my request, trained me to become a water technician.

For the first 10 weeks in Kenya, I lived in the central part of the country, attending classes every day, with the greatest focus on cultural and language training. At the end of that time, I was fairly proficient in KiSwahili, the national language. And then Peace Corps, in its wisdom, sent me out to the western part of the country to live and serve among the Luo peoples.

I wasn’t in my village but a few days before I realized that the Swahili I had labored so hard to master wasn’t quite the same Swahili the Luos spoke. I had learned classical KiSwahili; the Luos spoke something I later learned was called “dirty Swahili.” The former is highly technical and intricate; the latter is very simple and ignores all rules of grammar.

Which meant that my training, which had led me to believe that I could live and move and have my being among the Luo, was insufficient at best, a barrier at worst.

All this became crystal clear to me within my first week in my village. Wherever I went, whenever I spoke Swahili, people looked at me in confusion. I couldn’t communicate that well, despite my high score on my language exam.

Worst of all, I could not properly greet people.

And greeting people, in Africa as in much of the world, is a very important part of life. Whether you greet them … how you greet them … even if you are just walking down the street (or the dirt path, if you live in much of the developing world) … all of those things place you in society. So if you can’t properly greet people, you really don’t have a place … you don’t know where you belong … or even whether you belong.

One morning, as I was walking down a dirt road, an old woman – and I mean, an old woman, with frizzy little tufts of grey hair on her head and a face filled with wrinkles and dark, dark eyes that peeked out from between those wrinkles – one morning, this woman greeted me on the road.

“I see you,” she said.

I was so startled that she spoke to me in English that I didn’t respond at first. I simply while I thought, I see you? What kind of greeting is that?

So I responded in kind.

“Um, I see you?” I replied, questioningly.

The woman smiled at me and stood there and waited for me to go on.

“Um, how are you?” I asked, not knowing what else to say.

“I am here,” she said.

OK, I thought.

“I am here, too,” I replied, thinking, Isn’t that obvious? We’re standing in the middle of a dirt road, face to face. Of course you’re here. Of course I’m here!

“It is good to be seen,” she said.

And then we began to talk, mixing Swahili, the version I didn’t really know well, and DhuLuo, the tribal language that I really didn’t know yet, and English, which she didn’t know well, and somehow she managed to teach me that in her tribe, as in much of Africa, a proper greeting begins with, “I see you.”

The proper response is, “I am here. I see you.”

The one who began the conversation concludes the greeting with, “I am here. It is good to be seen!”

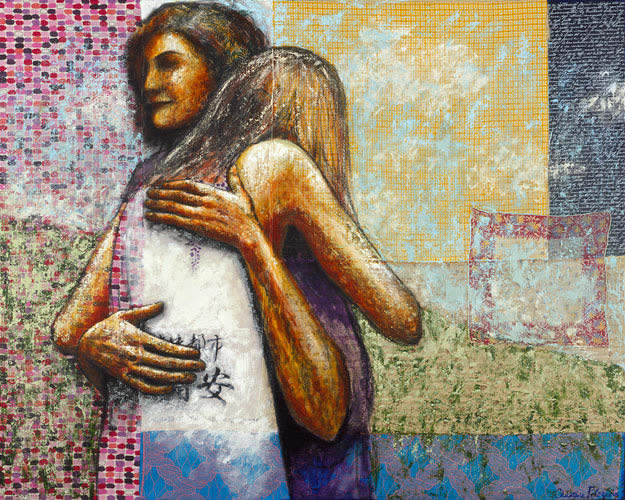

In much of Africa, this greeting is what gives people life and builds community. You don’t walk down the street and ignore people – you see them. And by seeing them, you do more than acknowledge their presence in the same piece of earth that you occupy. You acknowledge their whole being. You grant them meaning. You name them as part of your community.

As we parted, she in her direction and I in mine, I realized: I had just been introduced to a whole new way of being.

I was seen.

Therefore I belonged.

And I saw.

Therefore the other person belonged as well.

Yes indeed, it is good to be seen!

• • •

Seeing and being seen is what today’s Gospel lesson is all about.

We have Luke’s story of Zacchaeus, the wee little tax collector who was so anxious to see Jesus that he climbed a sycamore tree in order to see over the people in the crowd.

Now most of the time, the focus for this story is on Zaccheus giving away half his fortune and paying back four times what he might owe to people because he had defrauded them. That focus centers on Zaccheus’ conversion and subsequent repentance for the wrongs he had done.

But this story is not so much about repentance as it is about inclusion. Or, more accurately, about God’s wild, radical, inexplicable inclusion of all of God’s beloved children, no matter what the world might think of them or how the world might treat them.

Zaccheus, remember, was the chief tax collector in Jericho; therefore he was:

(a) Rich. Luke says so;

(b) Despised. Tax collectors, as all who witnessed this event knew, were employees of the oppressive Roman government. Any Jew who worked for the Romans was considered a traitor. Any Jew who collected taxes for the Romans, thus keeping the Romans in power, was a double traitor; and

(c) Pretty much an outcast in his own society. See (a) and (b) above.

So when Jesus calls Zaccheus down from the tree – where he really had no business being, since he was both a grownup and a powerful man – Jesus was setting, yet again, another example of God’s incredible love, even for those whom society does not love.

Jesus teaches us, yet again, that God’s love trumps society’s hate. You see, society would have preferred that Jesus ignore that little traitor up in the tree, and society expected the Jesus would never have gone to that little traitor’s house, much less eaten with him.

But Jesus never paid much attention to what society wanted, did he? Instead of letting society dictate to him, Jesus dictates to society. He declares who is good, who is worthy. He determines who belongs, who is part of the community.

So what if society despises this wee little man? Jesus doesn’t.

So what if society has judged this tax collector and found him wanting? Jesus doesn’t.

Instead, Jesus declares that Zaccheus is a son of Abraham – a beloved child of God!

Jesus saw Zaccheus and declared him good.

Take that, society!

Jesus demonstrates to and for us an in-your-face, I-really-don’t-care-what-society-thinks radical hospitality that declares, once and for all, that all of us – that each of us – is a beloved child of God. That all of us and each of us belongs to God. That our community is in and with and through God – because God said so!

How many times have we declared that someone is not welcome in our community, is not one of “us”? We’ve all done it – we decide that because someone is different, looks different, sounds different, smells different, that he or she cannot come in to our community.

And how many times have we been told that we do not belong, that we can’t come in, that we are not welcome in a community? That has happened to all of us as well.

But both stances – saying no and being told no – violate the very image of God in which we are created.

We are created in God’s image of love, because we are not necessary to God (God was before we were and will be after we are, so we can’t possibly be necessary), and God’s image of community (God the Father, God the Son, God the Holy Spirit, always together). Since God created us in God’s image, God gets to decide who’s in and who’s out. And since God never votes anyone off the island, and God never says, “You I love; you … eh …” we are called to do the same. To include people.

To see others – really see them …

… and to be seen.

I see you, Jesus said to Zaccheus

I am here. I see you, Zaccheus replied.

I am here. It is good to be seen! Jesus said.

Zaccheus’ story is a lesson in community – in God’s community, and how God wants us to be in community. It’s a reminder that we don’t get to make the rules; God does.

God sees each and every one of us, welcomes us into the household of God, makes room for us, sits down and eats a meal with us.

And then God asks us to do the same. God asks us to see each other not for what we think they are, but for what God knows they are: God’s beloved children.

It indeed is good to be seen!

Amen.

A sermon preached at Epiphany Episcopal Church, Richmond, Va., on the 23rd Sunday after Pentecost, 31 October 2010, Proper 26, Year C.