From The New York Times:

By BONO

Guest columnist

(Published: September 18, 2010)

I’ve noticed that New Yorkers, and I sometimes try to pass for one these days, tend to greet the word “summit” with an irritated roll of the eyes, a grunt, an impatient glance at the wristwatch. In Manhattan, a summit has nothing to do with crampons and ice picks, but refers instead to a large gathering of important persons, head-of-state types and their rock-star retinues in the vicinity of the United Nations building and creates, therefore, a near total immobilization of the East Side. Can world peace possibly be worth this? Never, never…Eleanor Roosevelt, look what you’ve done … .

Deirdre O’Callaghan

Bono

Recent global summit meetings, from Copenhagen to Toronto, have frankly been a bust, so the world, which may not know it yet, is overdue for a good multilateral confab — one that’s not just about the gabbing but about the doing. The subject of the summit meeting at the United Nations this week is one whose monumental importance is matched only by its minuscule brand recognition: the Millennium Development Goals, henceforth known as the M.D.G.’s (God save us from such dull shorthand).

The M.D.G.’s are possibly the most visionary deal that most people have never heard of. In the run-up to the 21st century, a grand global bargain was negotiated at a series of summit meetings and then signed in 2000. The United Nations’ “Millennium Declaration” pledged to “ensure that globalization becomes a positive force for all the world’s people,” especially the most marginalized in developing countries. It wasn’t a promise of rich nations to poor ones; it was a pact, a partnership, in which each side would meet obligations to its own citizens and to one another.

Of course, this is the sort of airy-fairy stuff that people at summit meetings tend to say and get away with because no one else can bear to pay attention. The 2000 gathering was different, though, because signatories agreed to specific goals on a specific timeline: cutting hunger and poverty in half, giving all girls and boys a basic education, reducing infant and maternal mortality by two-thirds and three-quarters respectively, and reversing the spread of AIDS, tuberculosis and malaria. All by 2015. Give it an A for Ambition.

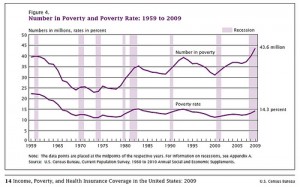

So where are we now, 10 years on, with some “first-world” economies looking as if they could go bang, and some second- and third-level economies looking as if they could be propping us up?

Well, I’d direct you to the plenary sessions and panel discussions for a detailed answer…but if you’re, eh, busy this week…my view, based on the data and what I’ve seen on the ground, is that in many places it’s going better than you’d think.

Much better, in fact. Tens of millions more kids are in school thanks to debt cancellation. Millions of lives have been saved through the battle against preventable disease, thanks especially to the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria. Apart from fallout from the market meltdown, economic growth in Africa has been gathering pace — over 5 percent per year in the decade ending in 2009. Poverty declined by 1 percent a year from 1999 to 2005.

The gains made by countries like Ghana show the progress the Millennium Goals have helped create.

At the same time, the struggles of places like Congo remind us of the distance left to travel. There are serious headwinds: 64 million people have been thrown back into poverty as a result of the financial crises, and 150 million are hungry because of the food crisis. And extending the metaphor, there are storms on the horizon: the poor will be hit first — and worst — by climate change.

So there should be no Champagne toasts at this year’s summit meeting. The 10th birthday of our millennium is, or ought to be, a purposeful affair, a redoubling of efforts. After all, there’s only five years before 2015, only five years to make all that Second Avenue gridlock worth it. With that in mind I’d like to offer three near-term tests of our commitment to the M.D.G.’s.

1. Find what works and then expand on it. Will mechanisms like the Global Fund get the resources to do the job?

Energetic, efficient and effective, the fund saves a staggering 4,000 lives a day. Even a Wall Streeter would have to admit, that’s some return on investment. But few are aware of it, a fact that allows key countries — from the United States to Britain, France and Germany — to go unnoticed if they ease off the throttle. The unsung successes of the fund should be, well, sung, and after this summit meeting, its work needs to be fully financed. This would help end the absurdity of death by mosquito, and the preventable calamity of 1,000 babies being born every day with H.I.V., passed to them by their mothers who had no access to the effective, inexpensive medicines that exist.

2. Governance as an effect multiplier. In this column last spring, I described some Africans I’ve met who see corruption as more deadly than the deadliest of diseases, a cancer that eats at the foundation of good governance even as the foundation is being built. I don’t just mean “their” corruption; I mean ours, too. For example, multinational oil companies. They want oil, and governments of poor countries rich in just one thing, black gold, want to sell it to them. All well and good. Except the way it too often happens, as democracy campaigners in these countries point out, is not at all good. Some of these companies knowingly participate in a system of backhanders and bribery that ends up cheating the host nation and turning what should be a resource blessing into a kind of curse of black market cabals.

Well, I’m pleased to give you an update on an intervention that some of us thought of and fought for as critical: hidden somewhere in the Dodd-Frank financial reform bill (admit it…you haven’t read it all either) there is a hugely significant “transparency” amendment, added by Senators Richard Lugar and Benjamin Cardin. Now energy companies traded on American exchanges will have to reveal every payment they make to government officials. If money changes hands, it will happen in the open. This is the kind of daylight that makes the cockroaches scurry.

The British government should institute the same requirement for companies trading in Britain, as should the rest of the European Union and ultimately all the G-20 nations. According to the African entrepreneur Mo Ibrahim, who has emerged as one of the most important voices on that continent, transparency could do more to transform Africa than even debt cancellation has. Measures like this one should be central to any renewed Millennium Development Goal strategy.

And the cost to us is zero, nada. It’s a clear thought in a traffic jam.

3. Demand clarity; measure inputs and outputs.

Speaking of transparency, let’s have a little more, please, when it comes to the question of who is doing what toward which goal and to what effect. We have to know where we are to know how far we’ve left to go.

Right now it’s near impossible to keep track. Walk (if you dare) into M.D.G. World and you will encounter a dizzying array of vague financing and policy commitments on critical issues, from maternal mortality to agricultural development. You come across a load of bureau-babble that too often is used to hide double counting, or mask double standards. This is the stuff that feeds the cynics.

What we need is an independent unit — made up of people from governments, the private sector and civil society — to track pledges and progress, not just on aid but also on trade, governance, investment. It’s essential for the credibility of the United Nations, the M.D.G.’s, and all who work toward them.

And that was the deal, wasn’t it? The promise we made at the start of this century was not to perpetuate the old relationships between donors and recipients, but to create new ones, with true partners accountable to each other and above all to the citizens these systems are supposed to work for. Strikes me as the right sort of arrangement for an age of austerity as well as interdependence. (The age of interrupted affluence should sharpen our focus on future markets for our sake as well as theirs.)

No leader scheduled to speak at the summit meeting is more painfully aware of this context than President Obama, who one year ago pledged to put forth a global plan to reach the development goals. If promoting transparency and investing in what works is at the core of that strategy, he can assure Americans that their dollars are reinforcing their values, and their leadership in the world is undiminished. Action is required to make these words, these dull statistics, sing. The tune may not be pop but it won’t leave your head — this practical, achievable idea that the world, now out of kilter, can re-balance itself and offer all, not just some, a chance to exit the unfathomable deprivation that brings about the need for such global bargains.

I understand the critics who groan or snooze through the pious pronouncements we will hear from the podium in the General Assembly. But still in my heart and mind, undiminished and undaunted, is this thought planted by Nelson Mandela in his quest to tackle extreme poverty: “Sometimes it falls upon a generation to be great.”

We have a lot to prove, but if the M.D.G. agreement had not been made in 2000, much less would have happened than has happened. Already, we’ve seen transformative results for millions of people whose lives are shaped by the priorities of people they will never know or meet — the very people causing gridlock this week. For this at least, the world should thank New Yorkers for the loan of their city.

Bono, the lead singer of the band U2 and a co-founder of the advocacy group ONE and (Product)RED, is a contributing columnist for The Times.