“When you first got here, did you cry a lot?”

A friend asked me that as I prepared to lead yet another wake service the other night, the fourth wake service of five this week, for the three funerals I did just this week.

She wondered if all the funerals we did in the first months after my arrival on the Rosebud Reservation caused me to crumple with grief.

“Wasn’t that overwhelming?” she asked.

I told her: It’s actually harder now, because I know so many of the people now. When I first arrived, I was burying strangers, people whose stories I did not know.

Now?

It seems I know most of the people I bury. If I don’t know them personally, I know their families.

I cry for those whom I bury … so many of them, young and old, often in bunches so close together that it seems that all I do is wakes and funerals, and wakes and funerals, and more wakes, and more funerals.

I cry for all the violence in the world: For the people of Yemen. And Gaza. And South Sudan. And Mexico. And Cameroon. And Haiti. And just about every place around the world where people settle arguments and confront fear with war.

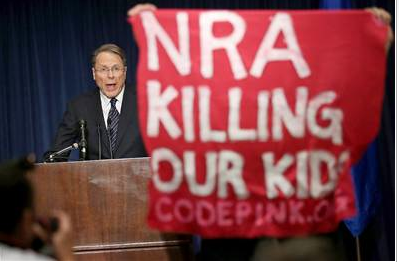

I cry for all the violence in this country. Right now, my tears are for the faithful Jews of the Tree of Life Synagogue in Pittsburgh. For Vickie Lee Jones and Maurice Stallard, two innocent African Americans murdered in a Kentucky grocery store simply because they were African American. For police officers gunned down while doing their jobs. For women killed by domestic partners who had no business having access to guns. For our soldiers and Marines killed in combat.

I cry for our children, especially this latest generation which one 18-year-old has labeled the “Massacre Generation,” because massacres – massacres! – make up the majority of their memories.https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/2018/11/01/i-am-i-belong-massacre-generation/?utm_term=.d09d6608d0a0

I cry for the migrants who so desperately want a better, safer life – and whose journeys end, instead, in death in the desert. Or separated from their children. Or thrown in jail. Or deported without their children.

The tears suddenly fill my eyes, and I have to take a deep breath, and – if I’m preaching – sometimes pinch my fingers together to make a focal point for my body.

I am not depressed.

This is not a medical issue that can be treated with drugs.

But I do have a big heart, a heart that sometimes is too filled with love, too filled with hope, too filled with a desire for goodness and grace and mercy and justice and simple kindness.

And then the tears come, unbidden.

I believe in the inherent goodness of humanity, that we, who are all created in the image of God, really are good people.

I believe in that goodness because I have seen it, because I see it every single day, when people reach out to help each other, when a friend unbidden reaches out to me and asks, “how are you doing today,” when another friend texts, “You are loved.”

I think that because I know there is goodness in the world, when I see the bad stuff – the shootings, the racism, the hatred, the vitriol, the fear-mongering, the blatant lies, the attempts to make some people lesser than others – my heart cracks and the tears come.

I don’t mind the tears.

They remind me that I am human.

They remind me of God’s love.

They push me to do better, to be better.

They remind me that I care.

They remind me to never stopcaring.

So, yes, I cry a lot these days.

And then I wipe away the tears.

I remember the quotation from the Talmud, tattooed around my left arm as a prayer: Do not be overwhelmed by the enormity of the world’s griefs. Do justice now. Love kindness now. Walk humbly with your God now. You are not obligated to complete the work, but you are not free to abandon it.

And with the tears wiped, I get back to work, to God’s work, trying as best as I am able to fulfill what Verna Dozier, quoting Howard Thurmans, called the “dream of God”: “A friendly world of friendly folk, beneath a friendly sky.”

enator Rounds, Senator Thune and Congresswoman Noem:

enator Rounds, Senator Thune and Congresswoman Noem: