Today is Good Shepherd Sunday, your patronal feast day, when we celebrate the fact that Jesus has proclaimed himself as our good shepherd, and the fact that we have said “Yes” to Jesus’ proclamation.

Now, we could spend the whole morning talking about sheep and how cute those little lambs are, and dispelling the myth that sheep are stupid (they’re not and we know it. Goats are stupid; sheep are smart), and how much we don’t like being called sheep, yadda, yadda, yadda.

But you all know sheep, because so many of you raise them here. For y’all, sheep are, for the most part, a commodity, a way of making a living. And those of you who have been shepherds? Or who know shepherds? You don’t need me to explain sheep to you.

So instead, let’s talk about wild sheep.

I was shocked to discover how many kinds of wild sheep there are out there.

There are the ovis ammon, the wild sheep of the semi-desert regions of central Asia; these are the ones known as Marco Polo sheep …

… the ovis vignei, or the urial, the bearded reddish sheep of southern Asia.

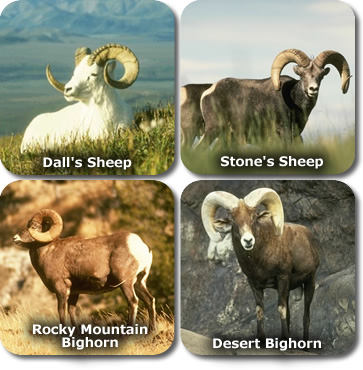

… the Dall sheep, also known as the ovis Montana dalli, which are the large, white, wild sheep of northwestern Canada and Alaska …

… the Ammotragus lervia, the Barbary sheep of northern Africa …

… the ovis Canadensis, also called the Rocky Mountain bighorn and Cimarron, which are the wild sheep of mountainous regions of western North America with the massive curled horns …

… and the ovis musimon or moufflon, the wild mountain sheep of Corsica and Sardinia.

That’s a lot of wild sheep. I actually didn’t even think of some of them as sheep until I looked them up. To me, Bighorns are bighorns, not sheep.

And who watches over all these wild sheep?

Well, there’s the Wild Sheep Foundation … the Grand Slam Club … the Eastern Chapter Wild Sheep Foundation, the Idaho Wild Sheep, the Foundation for North American Wild Sheep, the Bighorn Sheep Society of Idaho, the Northern Wild Sheep and Goat Council, the Wild Sheep of North America – Bighorn Institute, the Utah Foundation for North American Wild Sheep, and the Washington Wild Sheep Foundation. And those are just the groups that I found. Lord knows how many other groups there are out there, watching over these sheep in one form or another.

Why do these wild sheep need these groups to watch over them?

Because they don’t have a shepherd.

Because while wild sheep are communal … they stick together, they raise each other’s lambs … they have no leader. There is no one ram or ewe to guide them.

There is no voice calling them. No one feeds them. No one waters them. No one guards them against predators.

Wild sheep are on their own.

So on this Good Shepherd Sunday, perhaps we need to pay less attention to Jesus’ proclamation that he is our Good Shepherd (because we’ve already agreed to this), and more attention to his proclamation that there are other sheep out there – wild sheep – who do not yet belong to his fold, and that he’s going to bring them also, and they will listen to his voice.

Today’s Gospel, my friends, is not about us.

It’s about all those wild sheep out there …

… and the fact that Jesus is actively looking for them.

Lord knows, those sheep, those wild sheep, need to hear Jesus’ voice right about now.

Think about all the voices that abound in our society … voices singing their siren songs about getting ahead (and leaving others behind) … that make impossible and irrational promises (does anyone here really believe a car will make you sexier? A car?) … that spew hatred and condemn civil discourse …

It’s no wonder so many sheep are wild these days.

It’s no wonder that the latest surveys show that more and more young people in this country claim to be “spiritual” and not “religious.” How could they be anything but “spiritual and not religious” when the only voices they hear are ones of discord and discontent, of maliciousness and hatred, of vituperative dismissal of anyone who dares to disagree with the speaker?

With all that negativity being spewed about, how is it even possible for Jesus’ voice – the voice of God proclaiming, “I love you” – to be heard?

You all are the Church of Good Shepherd, nestled in this little valley town (town? village?) of Blue Grass, in Highland County, hard up against the West Virginia border. What are you doing to make Jesus’ voice heard?

This is your call, in this time and in this place. This is why you are called the Church of the Good Shepherd – to make the Good Shepherd’s voice heard, above all the babble and nonsense that fills our ears every moment of every day.

It is all well and good for us to say, “Well, we have a good shepherd. We have the Good Shepherd.” But if all we do is rest on our laurels and never do anything with this knowledge, we’re in trouble. Because Jesus is clear: There are others who do not belong to the fold, and he fully intends to go get them as well, so that they, the wild sheep, can hear his voice over the cacophony that threatens to deafen us today.

As one of my favorite theologians says, “This is part of what it means to be the Body of Christ – to remind each other of God’s promises and speak Jesus’ message of love, acceptance, and grace to each other … [so that] we’ll find the courage to [speak Jesus’ message of love, acceptance, and grace] to others in our lives as well.”[1]

And we are the ones who are to be his voice … in this time, in this place.

We who already belong to the fold are to stand up for Jesus always, to invite others in … sometimes by speaking Jesus’ words of love, sometimes by living Jesus’ life of love.

We have to live our lives in such a way that others who have not yet heard Jesus’ voice can hear it through us and say, “I want what you’ve got.”

With all that we are and all that we have and all that we say and all that we do, we are the ones called to love in truth and in action, every moment of our lives.

Today is Good Shepherd Sunday, y’all’s patronal feast day. It is a day – the day – to celebrate the fact that we have the Good Shepherd in our lives, who knows us each by name, who calls us, guides us, feeds us, waters us, loves us.

It is also the day when we are called – specifically – to go into the world, to find those wild sheep who are hearing a plethora of voices but not the voice, and to be that voice to and for them.

Because believe me – there are wild sheep out there. Jesus is looking for them. And he’s counting on us to bring them home to his fold.

Amen.

• • •

This sermon was created via discussions with my friends The Rev. Laura Minnich Lockey, Betsy Heilman, Amber Parsons-Zack, Laura Lynn Batelli and Kathleen Merrill Jackson.

Sermon preached on the Fourth Sunday of Easter, 29 April 2012, Year B, at the Church of the Good Shepherd, Blue Grass, Va.

[1] David J. Lose, Marbury E. Anderson Biblical Preaching chair, Luther Seminary, St. Paul, MN, “Abundant Life,” http://www.workingpreacher.org/dear_wp.aspx?article_id=581