Luke 16:19-31

I am a rich person.

I know this because I looked it up on globalrichlist.com, where I entered my income from last year and discovered that I rank in the top 13.74 percent of the wealthiest people in the world.[1]

According to this web site, I am the 824,785,999th richest person in the world, this out of the approximately 6.8 billion people now living.

That is an amazing ranking, isn’t it? I was astonished when I found out how rich I am, when compared to the rest of the world.

At the same time, I also am a poor person.

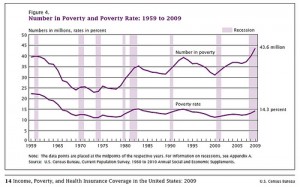

I know this because I looked in the Census Bureau’s Poverty Report that was released a few weeks ago.

According to that report, I am incredibly poor. I am so poor that I inhabit, according to the Census Bureau, something called the “poverty universe,” along with more than 40 million other Americans.

One report says I am rich. The other says I am poor.

Let me clear this up for you a bit: For the last five years, I have been an Appointed Missionary of The Episcopal Church. I served for four years in the Diocese of Renk of the Episcopal Church of Sudan, and for about one year in the Diocese of Haiti. During that time, I was paid, by The Episcopal Church, $6,000 per year. $500 per month. I raised money during that time to help support me, so for both of those reports I consulted, I raised my income to $8,000 last year.

On a worldwide scale, I am rich.

In the “poverty universe,” I am poor.

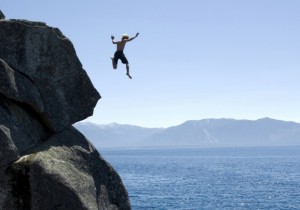

Somehow, I have managed to span the great chasm between rich and poor, the chasm of which Jesus speaks as he tells the story of the Rich Man and Lazarus in Luke’s Gospel.

The story he tells is not a new one. It is, in fact, much older than Jesus himself, coming out of the Egyptian tradition. But regardless of its age and provenance, the story Jesus tells is an important one, not just for the disciples and Pharisees who are listening then, but to us now.

Let’s get something straight right off the bat: Jesus – God – has no problem with wealth. We know that because the Bible tells us so. In this very story, Lazarus, the poor man who had been abandoned outside the gates of the unnamed rich man, is sitting next to Abraham, the patriarch of the people of Israel and indeed of the three great faiths of the world. Abraham was a very wealthy man, far beyond simply being rich. He had land, animals, money … By reading that Lazarus, a poor man in such bad shape that he was covered in nasty sores, so weak that he was licked by dogs (that most despised of animals), simply by reading that Lazarus is sitting in paradise next to Abraham, we know that wealth in and of itself is not a bad thing in God’s eyes. By hearing Abraham tell the rich man, “Sorry, you’re out of luck, Lazarus can’t help you,” we know that in God’s eyes, Abraham the wealthy man is also Abraham the exalted man.

So wealth is not the problem that Jesus is highlighting in this story.

What Jesus is focusing on is the great chasm between wealth and poverty, between those who have, and those who do not have.

For it is that chasm that gets in the way of God’s will being done in God’s very good creation.

I know a lot about this chasm. I knew a lot about this chasm before I went online and found out that I am simultaneously rich and poor. In my time as a missionary, I have lived among some of the poorest people on earth. I have seen the poverty, and I know what it is like to be on the wrong side of the chasm.

In South Sudan, I lived in a mud hut, with no running water, very little electricity, lots of disease, limited food to eat. And I lived a life of privilege in Sudan, compared to the average person, who lived in a hut made of grass, who had no electricity ever, no clean water and no way to clean the water she had, frequently far too little to eat and no way to make enough money to ensure her children could grow up healthy and strong. I once had to explain to some U.S. government officials who wanted to learn what life was like in South Sudan that, no, there really was no functioning economy there, that most people were poor beyond belief, that there was never enough of anything, and no hope of getting any more. The Americans simply shook their heads in disbelief.

In Haiti, I lived in the poorest nation in the Western Hemisphere. The area in which I lived was surrounded by terrible slums, where people had very little, and even less hope of getting any more, while at the same time they were surrounded by people of wealth. Compared to my life in Sudan, my life in Haiti was full of riches. But when my colleagues saw where I lived, and how I lived, they could only shake their heads and ask me why. Why didn’t I have electricity all the time? Why did I haul water up three flights of stairs? Where was my air conditioner? My TV? (Hint: No electricity, no AC, no TV.)

So I know something, quite a bit, actually, about the poverty that Jesus is attacking in this story we call “The Rich Man and Lazarus” but which one commentator says more accurately should be called “The-Indifferent-Man-Who-Could-Have-Listened-to-Moses-and-the-Prophets-and-Followed-God’s-Way-of-Life-and-Been-Welcomed-Into-Paradise-by-Father-Abraham-But-Chose-Not-To and Lazarus.”[2]

The rich man, who is given no name in this story, knew what he was supposed to do. The Torah, the Five Books of Moses, told him: Care for the poor, the sick, the widows and the children. Leviticus says to love God with all your heart, mind, soul and strength. Deuteronomy says to love your neighbor as yourself. You cannot do the former if you do not do the latter. The Prophets who came after Moses said the same thing. Micah asks, “What does the Lord require of you, o mortal, but to do justice, love kindness and walk humbly with your God?” (Micah 6:8) Proverbs say that “If you close your ear to the cry of the poor, you will cry out and not be heard.” (Proverbs 21:13) Isaiah quotes God thundering, “What do you mean by crushing my people, by grinding the face of the poor?” (Isaiah 3:15) followed by a promise from God to never forsake them. (Isaiah 41:17) Jeremiah laments: “For the hurt of my poor people I am hurt, I mourn, and dismay has taken hold of me.” (Jer. 8:21), then asks, “Is there no balm in Gilead? Is there no physician there? Why has the health of my poor people not been restored?” (Jer. 8:22) Ezekiel proclaims: “This was the guilt of your sister Sodom: she and her daughters had pride, excess of food and prosperous ease, but did not aid the poor and needy.” (Ezek. 16:49)

Moses and the Prophets continuously spread God’s word: We are to care for the very least among us.

In telling the story of the rich man and Lazarus, Jesus continues in that same prophetic vein:

You see someone in need, you help him.

You feed the hungry. Give water to the thirsty. Make the lame leap for joy, the blind see, the deaf hear, the mute speak. Visit the sick and those in prison. Clothe the naked.

Lord knows – and it is true, God truly does know – that there is a great chasm in this world between the rich and the poor, between the have’s and the have-nots. You and I know it, you and I have seen it, some of you and I have lived in it.

But just because it exists does not mean we can’t do something about it.

Rich or poor – or both, if you are like me – we can cross that chasm – in this life – and we can do something about it, if we so desire. In this country alone, more than 44 million of us inhabit what the Census Bureau now calls the poverty universe. More than 85 percent of the world inhabits that same universe.

Is that what we want?

Is that what God wants?

The real question we have to ask ourselves this morning is this:

Are we willing to cross that chasm ourselves?

The only way to answer that question is to figure out what exists in our lives that keeps that chasm there, and keeps us from crossing it. We may not want to cross it because the poor are too much like Lazarus, covered in ugly sores, so weak that the dogs – the dogs – are able to lick his wounds without hindrance.

We may not want to cross the chasm because to do so would mean leaving our comfort zones, and we are afraid.

We may not want to cross the chasm because we may feel, in our deepest secret places, that sometimes, the poor deserve what they have, or rather, what they don’t have. We may feel that far too many of the poor are poor simply because they refuse to work.

(But know this: In this story that Jesus tells, Lazarus is so far gone that he didn’t go to the rich man on his own to beg. He was placed there because he was so far gone that the people who put him there knew the rich man was his last hope. So in this telling, Jesus is quite clear that he is not talking about people who refuse to work; he is talking about people who cannot help themselves.)

Whatever reasons we may have for not wanting to cross the chasm, we have so many more for doing so.

It doesn’t take much to become poor; we all know that. The economy in this country and around the world went from riding high to sinking like a lead balloon almost in the blink of an eye. We all know someone – and generally more than one someone – who lost their jobs, and then their savings, then their homes. Going from being a rich person to poor, which is so often outside our control, is frighteningly easy. In other words, one very personal reason for crossing the chasm is that because we could have been, and still might be, the ones on the far side, the ones who need help.

It doesn’t take much to become poor; we all know that. The economy in this country and around the world went from riding high to sinking like a lead balloon almost in the blink of an eye. We all know someone – and generally more than one someone – who lost their jobs, and then their savings, then their homes. Going from being a rich person to poor, which is so often outside our control, is frighteningly easy. In other words, one very personal reason for crossing the chasm is that because we could have been, and still might be, the ones on the far side, the ones who need help.

We know, too, that while there is nothing wrong with being rich – however you define that term – there is something wrong, in God’s eyes, with not using our wealth to help others in need. We may not be in a position to join Warren Buffet and Bill Gates and all those other billionaires who are giving away half their fortunes, but surely we are able to give something to those who have less.

And we may not be the ones who are called to work directly with the poor. Our call may be to use our wealth – however big or small – to help others help the poor. There is nothing wrong with that – each of us has different gifts, and some people’s gift is to fund the work of others.

Whatever our gifts are, the important question we always have to consider is this: Do we want to cross the chasm?

Because that surely is what Jesus is calling us to do today.

To make the leap of faith and cross the chasm.

Are we willing?

Amen.

[2] The Rev. Dr. George Hermanson, “Paying Attention,” on David Ewart’s www.holytextures.com,